THE PHOTO

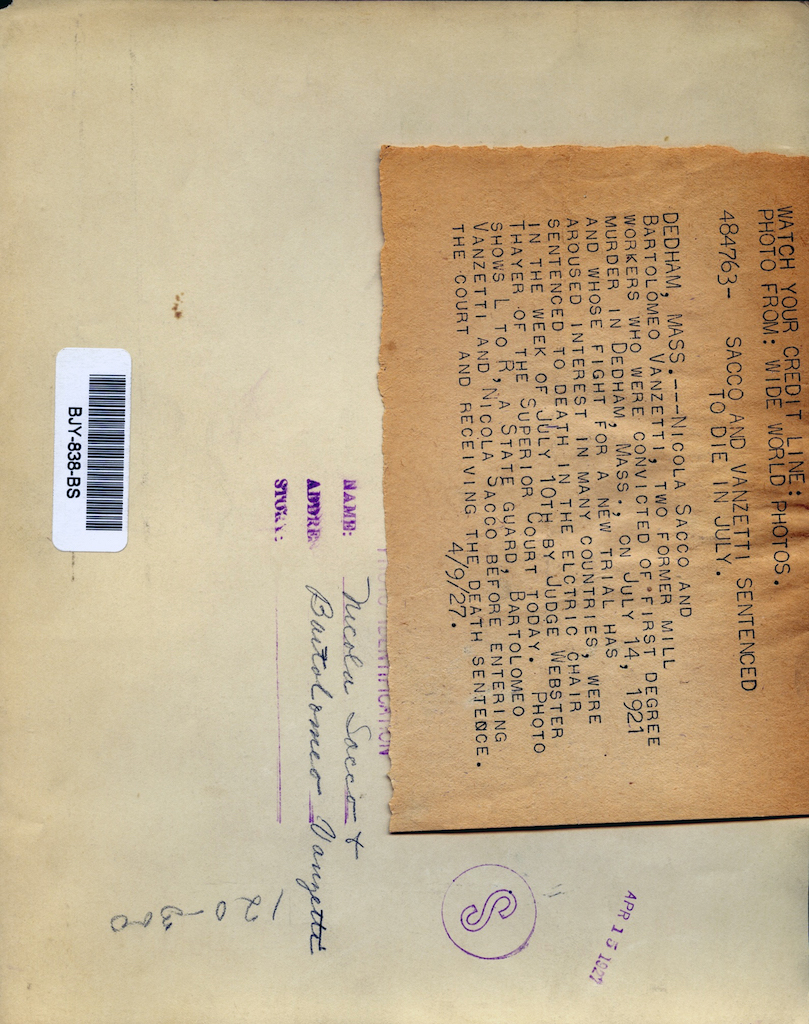

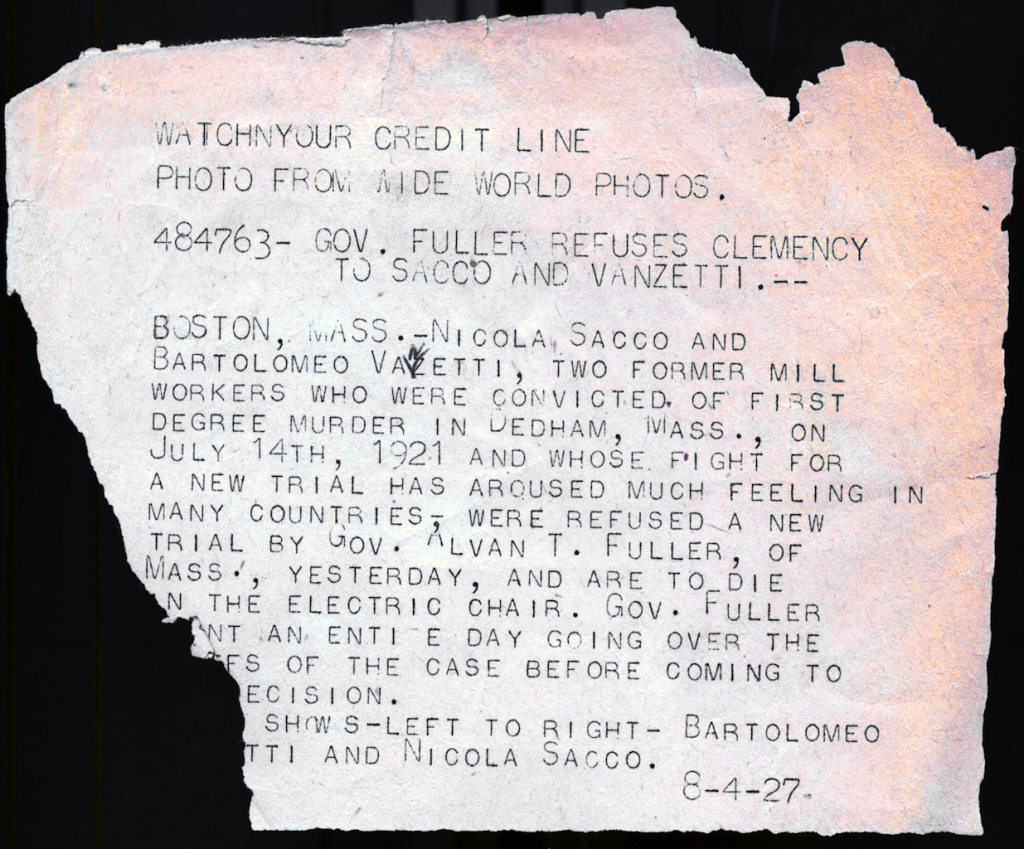

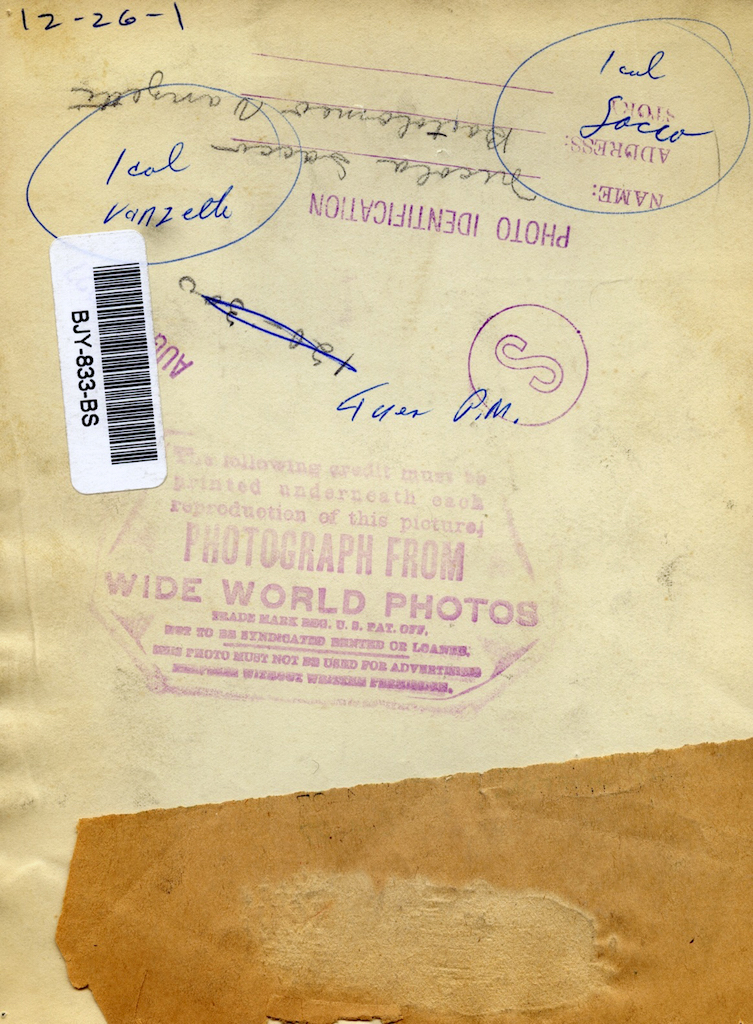

The photo was taken by a photographer of the Wide World Photos in Dedham, Massachusetts, on the morning of April 9th, 1927, around half past nine. Bartolomeo Vanzetti (with the mustache) and Nicola Sacco, handcuffed, are entering the court of the county of Norfolk, where Judge Webster Thayer will condemn them to death. In around twenty seconds several photos were taken by the same hand but this one only shows the face of Nicola Sacco with a warm smile. Most of the photos of the Wide World Photos on the Sacco and Vanzetti case – but not this one – were bought by Otto Bettmann and became part of the Bettmann Archive, the most important photographic archive of American history. In 1995 the archive was acquired by the photographic agency Corbis. The photo also appears cropped and processed for publication in a newspaper on August 23rd, 1927. It corresponds to those of the photographic archive of the Baltimore Sun and it is reasonable to assume (the archive of the newspaper is online only since 1990) that the two portraits accompany the article on the death of Sacco and Vanzetti. This latter photo shows the work of the editorial staff in preparing the material in occasion of the execution of the two anarchists that took place in the night between 22nd and 23rd August 1927.

The dating of the photo is fairly simple, despite the disorder of the dates indicated in the descriptions of other different prints, which refer to the need for editorial (in one it’s written 8/4/1927 – August 4th, 1917 – the day following that on which the Governor Fuller confirmed the death penalty, while Sacco and Vanzetti were in prison; in another it indicates 9th April 1927 (4/9/1927), and then, 15th April 1927, some dates are regarding the printing in newspapers, others refer to the date of the photo). In fact, there are also photos of the same scene taken from slightly different angles and all refer to the 9th April, 1927, the day of the death sentence pronounced by Judge Thayer in Dedham. The photo also appeared in The New York Times, in the Sunday edition of April 10th, 1927, on page 26. Whatever the reason, the photo testifies a tragic story, that of the trial and condemnation of two Italian anarchists in an America obsessed with the fear of the “red”.

THE STORY

When the photo was taken Sacco and Vanzetti were about forty years old and were already well known around the world.

Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco (the first was born in Villafalletto, near Cuneo, on 11th June 1888; the second in Torremaggiore, in the province of Foggia, on April 22nd, 1891) and emigrated to the US in 1908, at a time of acute crisis for the countryside and the South. They did not know each other but soon met among the “subversive” Italians in America and together joined the group of Luigi Galleani, who advocated “direct action” – attacks, violence, aimed to terrorize, to “expropriate” and strike the ” tyrants and oppressors “- and that was now, after the war, one of the most active and feared groups, especially on the East Coast of the United States.

The time – between 1919 and 1920 – is that of the biggest fear of the reds and of the attempts to prosecute and deport revolutionaries and subversives. The climate is – as in Europe, for that matter – tense. Not a day went past where there are no conflicts, strikes, arrests, expulsions. The Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer suffered a series of attacks and triggered a wave of police actions towards the “Bolsheviks”. In February 1920 Andrea Salsedo, an anarchist “galleanist”, is arrested, accused of subversive propaganda. Two months later, without hearing anything more about him, he fell from the 14th floor of the Bureau of Investigation in New York and died. Killed? Committed suicide? Fallen? His fate, similar to that of Giuseppe Pinelli, is still waiting to be explained.

They are the same days when, in upstate New York, in the industrial suburbs of Boston, several robberies of valuables of some companies take place. The offenders for most of them were not found even if the public smelt the smell of subversives, reds, Bolsheviks: all, invariably, recent European immigrants. There were real gangs, like the Morelli brothers’ one; but there were also measures of “self-financing” by anarchist groups.

On the morning of April 15th, 1920 – it is Thursday, payday – in Braintree, Massachusetts, two armored cars, Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli, are attacked, killed with a gun and robbed by a group of men in a dark Buick.

The police grope in the dark: Italian anarchists are suspected (Ferruccio Coacci and Mario Buda, who immediately flee to Italy) but the investigation does not seem to be a success. Then, following the slight trace of the car used in the robbery, they arrest Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, who are in a car of the tram and are returning home after meeting their comrades.

They are armed, but initially deny it. They are afraid; lie about their political affiliation. Their excuses are weak. Vanzetti is also charged with taking part in another similar robbery a few weeks before. The trial will take place between summer 1920 and that of 1921. The jury will declare Sacco and Vanzetti guilty of murder and robbery.

The court case takes place in chaos: attacks (the worst in New York, in September 1920: 38 dead and hundreds injured by a bomb on Wall Street), and xenophobic demonstrations which does not even escape the judge who presided the trials, pressure of the public opinion divided immediately between an array of international solidarity with the two anarchists and a compact front demanding exemplary sentences.

Witnesses hardly speak English; Judge Thayer appears motivated and aggressive; despite the approximations of the police investigation, the college of defenders – changed several times during the trial – does not appear able to prove the innocence of Sacco and Vanzetti.

On 21st July 1921, the two are convicted.

International action that unfolded then was enormous. America was considered by the left wing around the world (socialists, communists, anarchists, civil rights advocates) as the country that stamped on modern law. Two poor immigrants, one that made ends meet as a fishmonger, the other shaping heels in a shoe factory, would be condemned – to death, this was foreseen by the Code of Massachusetts – for their ideas, persecuted for a crime that they had not committed. Authors, intellectuals, artists, demonstrations, rallies shook the world asking for a new trial and condemning the American legal system.That, truthfully, sought, with a number of unsuccessful referrals, to adjourn the trial while accumulating new evidence, new witnesses, new enquiries by the defense. All rejected by Judge Thayer that afterwards did not receive a very flattering judgement from the Supreme Court judgment on his personal conduct, but received confirmation of his action as a judge. Under the pressure of the public opinion and in a last attempt to search for the truth, Massachusetts’ Governor, Alvan T. Fuller, appointed a committee of wise men (prestigious judges, professors of Harvard and of the MIT) that was hailed as a victory by the deployment in favor of Sacco and Vanzetti. But even this judgment was negative. The death sentence was confirmed on 22nd August 1927 and executed by the electric chair.

We do not know if Sacco and Vanzetti were innocent or guilty. The discussion (essentially useless, because every posthumous consideration can be contradicted by opposing posthumous considerations) continues since nearly a century. Some wanted their comrades to distinguish between Sacco – certainly unconnected with the facts – and Vanzetti – probably not unconnected with the facts. What is certain is that they did not have a fair trial.

The discussion of the case took place in the midst of turmoil, conflicts, accusations of hate and prejudice that ended up making the process “exemplary”. When the word “exemplary” resonates around the courtrooms, the defendants have good reason to worry. And all of us with them.

Even in the most solid and advanced democracies, actually, especially in them, the general public also plays a role in criminal proceedings that, if the court is not able to fly high in the sky of justice, is likely to be prominent with respect to the fair trial. The cases of the years closer to us, the trials of politicians accused of corruption and those of Islamic militants accused of terrorism, show how terrible the responsibility of judges that are not able to free themselves from the stream of public opinion and maintain the discretion and their own impartiality of their office can be.

Judge Thayer is a textbook example: one to gossip, fond of pubs and no stranger to the xenophobic nationalism, intended to give (and succeeded very well) the impression that under his leadership the jury would have given Sacco and Vanzetti a guilty verdict and that at the right time he would have condemned them to death. He succeeded, but he opened a wound that is still bleeding.