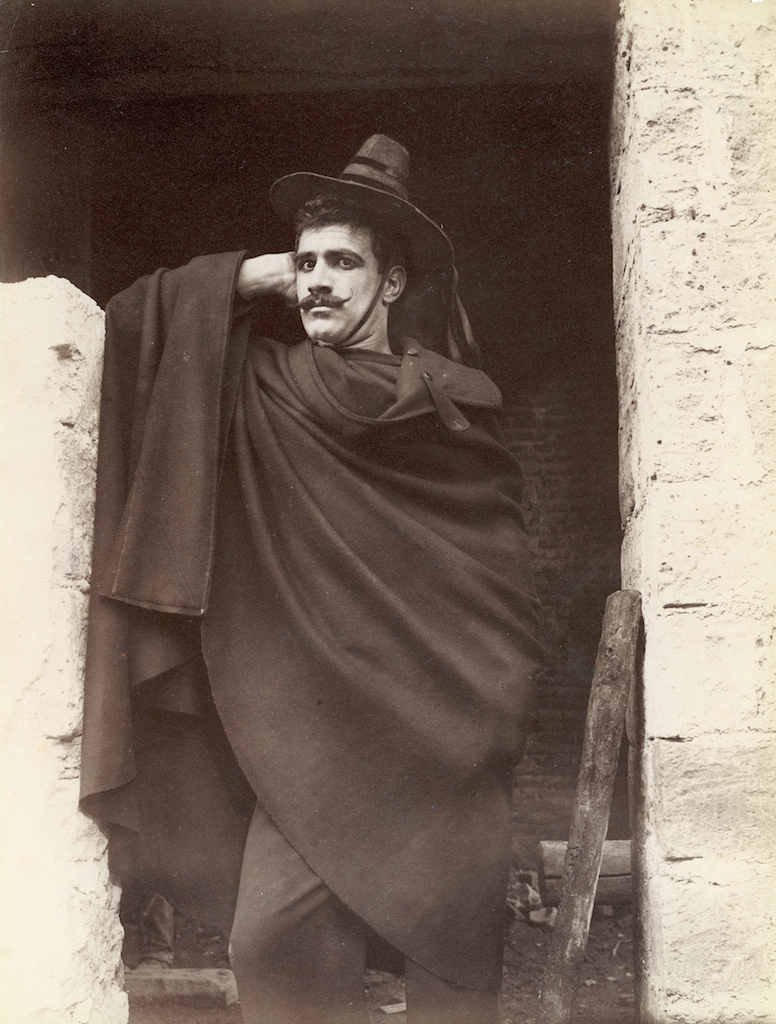

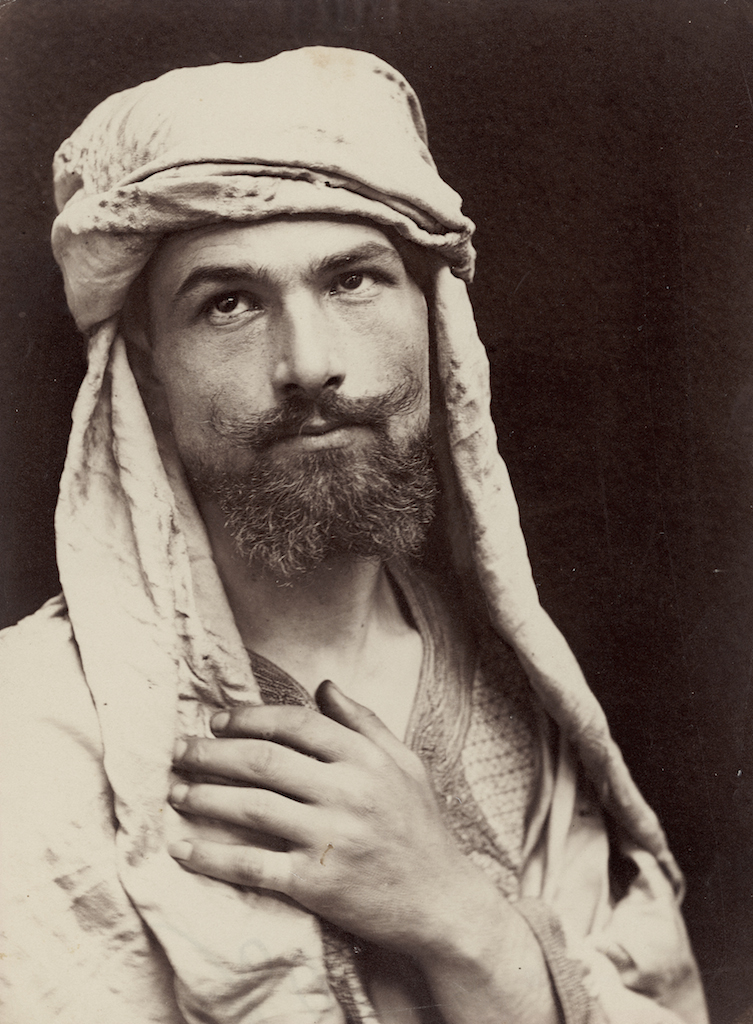

Wilhelm von Gloeden was twenty-two when, in 1878, he arrived in Taormina. He studied art in Weimar and was suffering from tuberculosis. After leaving the family, gentry of Mecklenburg, a century after Goethe, he discovered the country “where the lemon trees bloom”. He painted, but was attracted by the new art: photography. His cousin Wilhelm von Pluechow, protophotographer of portraits and nudes in Naples seems to have suggested, on the way to Mount Etna, that one could also live out of photography: he did. And the young descendant of the Gloeden barons landed in Sicily and came into contact with intellectuals, like himself, and photographers such as Giovanni Crupi and Giuseppe Bruni who mastered physics and chemistry to obtain photographic prints. With teutonic stubbornness he puts himself to work. He watches, he learns, he experiments alchemical formulas and innovative printing systems right up to “patenting” a method (the one of the negatives on paper touched up on the back in pencil) that will allow him to achieve contact positives of extraordinary singularity and smoothness. His taste for the pictorial also leads him to produce prints on watermarked paper, matching the red brick colour which make some of his photos appear as from lithographic origin and to practice collotype, the printing system then in vogue, with great skill. Gloeden photographs everything. Naturally, landscapes, in which he positions humans to facilitate the three-dimensional reading of the result; naturally, genre scenes, in which he documents customs and attitudes of that Sicilian world that Verga had also told in words and pictures and, on several occasions, also becomes a reporter taking those photographs of the consequences of the earthquake in Messina in 1908, that will appear in the great album, published the following year by the Società Fotografica Italiana (Italian Photographic Society).

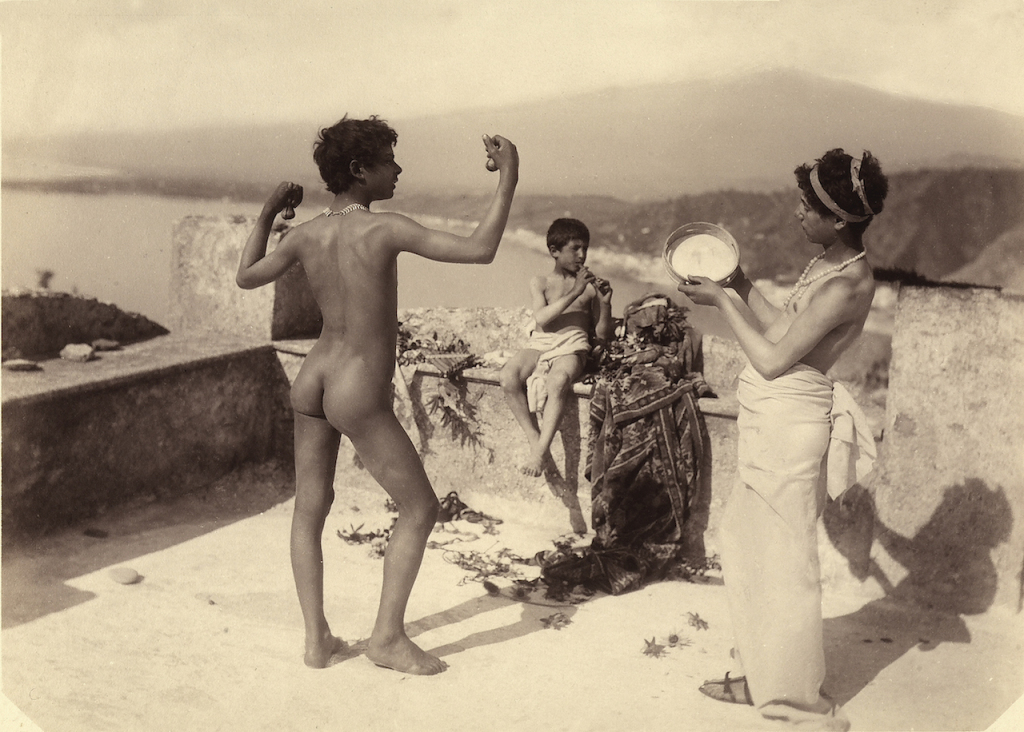

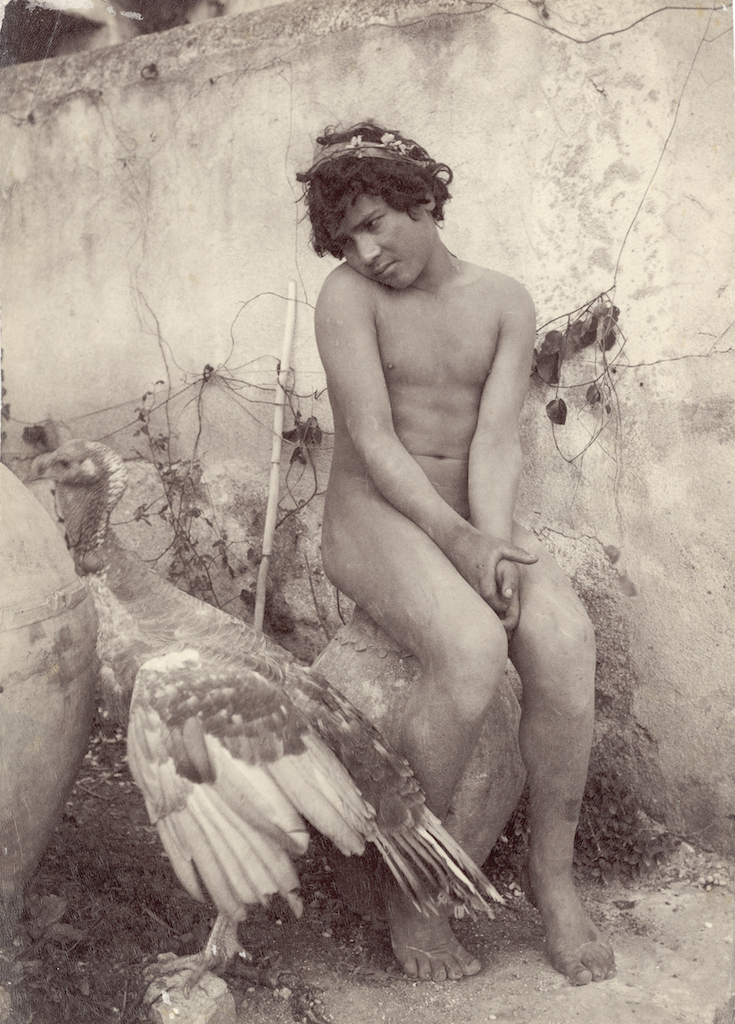

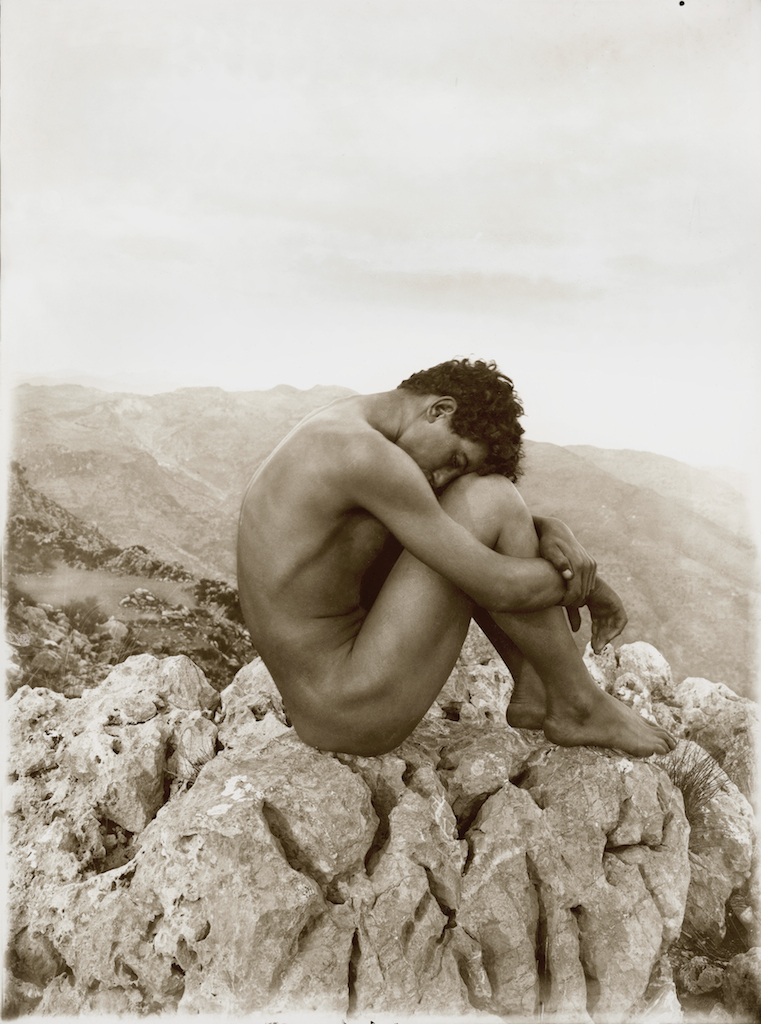

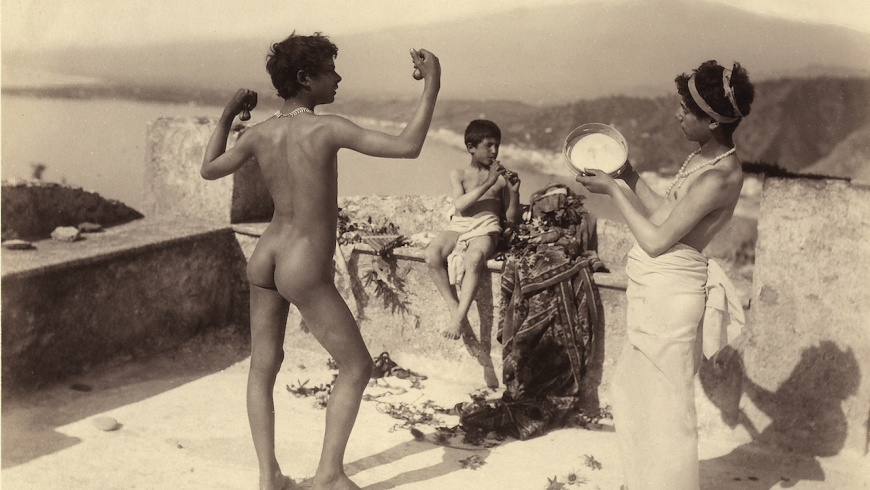

But his most famous photos are attempts, well managed, to revive the myth of Greek beauty and, however, classic. Mongibello then becomes the Olympus and children and less frequently girls who posed for him become fauns and maids. With the help of his half-sister, Sofia Raab, he produces tableaux vivant with simple scenes, but cleverly assembled, which often include ruins that are not lacking in the area. The subjects are often naked. Do they make sensation? Not officially. Certainly, there will have been murmurs about the work (which became the antique passion from 1895, when the family suffered a financial meltdown and Gloeden had to invent a profitable profession) of the good looking baron, but nudity was of everyday life at the seaside and the Baron was certainly generous with the models, and thus with their families, and money has always bought official silence. There were whispers of homosexuality, but no one is scandalized that much. He hosted Oscar Wilde and the King of Siam, Edward of England and Augustus of Prussia, Eleonora Duse and representatives of the great tycoon families of the moment, from the Krupps to the Rothschilds, the Morgans to the Vanderbilts. All are attracted by the sun of Sicily and by the photographs of the baron who meanwhile has won awards in the most important European exhibitions and have been consecrated as “artistic” with the publication, in 1897, in Camera Notes, the legendary New York magazine by Alfred Stieglitz. Even the Ministry of Education in Rome becomes aware of Gloeden’s work and in 1906 awards him with a gold medal. The images that some people still judge indecent are indeed naive, even disconcerting. Italo Zannier, the most meritorious Italian historian of photography, wrote: “His nudes are naive and like those of Mapplethorpe are sterilized by the beauty.”

In the house laboratory in Taormina Gloeden’s work is regular. The photos are sold to the potent and to tourists. The young Pan and the views of the Greek theater end up in postcard size in the boxes of the Royal Mail as the support of “Greetings from Sicily” sent by hikers from all around the world to friends back home. When, in 1931, Gloeden dies, his archive of plates and prints is inherited by his trusted assistant Pancrazio Bucini, modest photographer who continues the work of the “stationer”. At least until a zealous officer of the court of Messina, with a “bug” in the buttonhole of his jacket, tries to indict him as a disseminator of pornography. After a trial lasting three years, Bucini is acquitted from the crime of having overstepped the limit of “common decency”, but a large number of plates and vintage prints went lost or destroyed in the meantime. In 1978 in Spoleto, during the Festival, the collector and art historian Lucio Amelio expones part of the original photographic fund which had come into his possession and Gloeden becomes the inspiring model of avant-garde artists such as Warhol and Beuys.