The Barnum reader already knows Dr. Paul Wolff, one of the most innovative photographers of the first years of the 1900s (www.barnum-review.com/it/portfolio/dr-paul-wolff-il-principe-del-glamour/). Cultured, eclectic, impeccable in shots and … a good entrepreneur of himself.

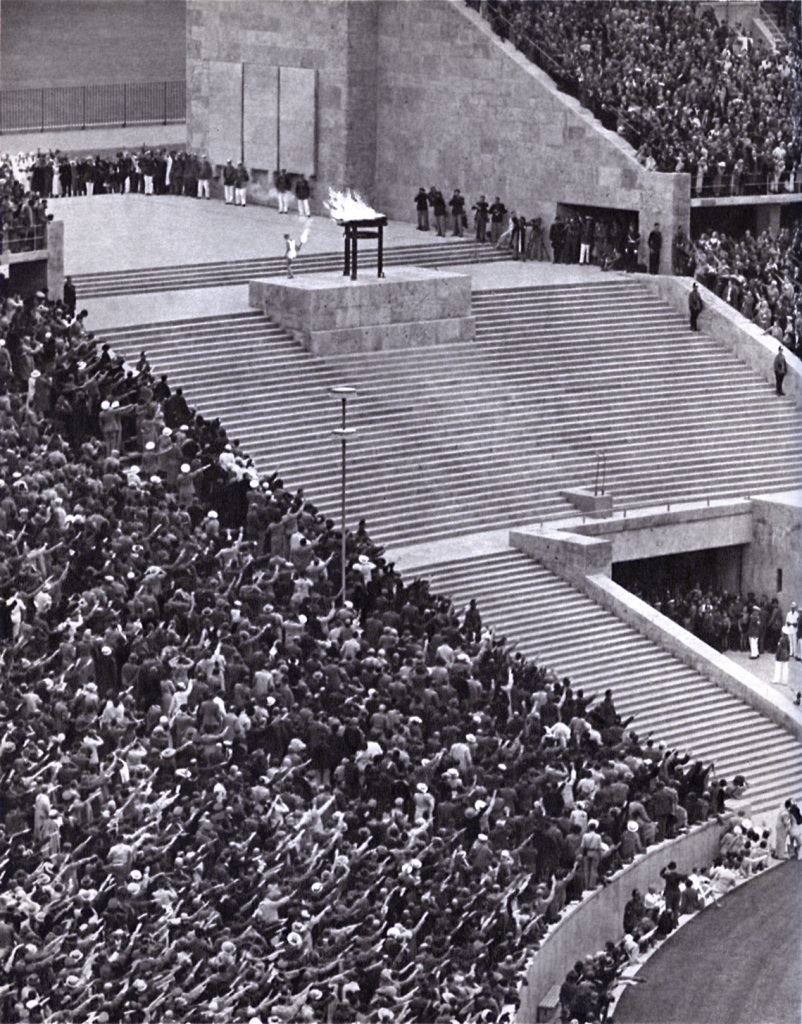

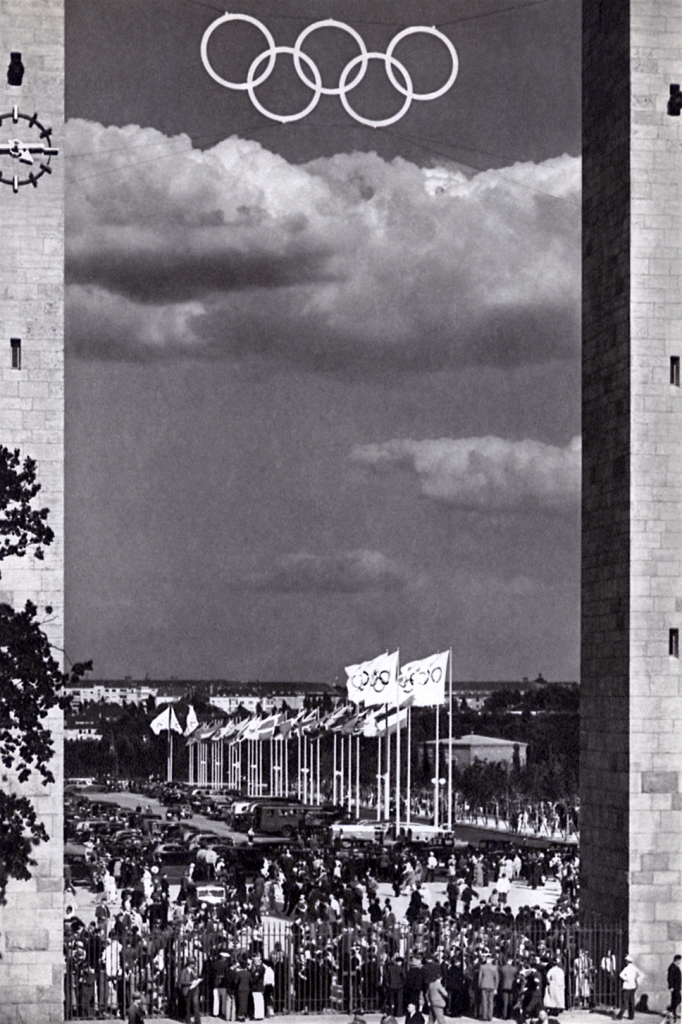

When, in Berlin, in August 1936, the Olympic Games are celebrated, the 11th of the modern era, Dr. Wolff cannot miss it. He does not show up alone. He brings a small staff with him: the photographers of his agency. First, the faithful Alfred Trischler to whom he entrusts the difficult task of grasping what is happening in the fields. But he will be based in the press room and will wander through the crowd to document, with his keen eye that leaves no recourse, the “reverse shot”.

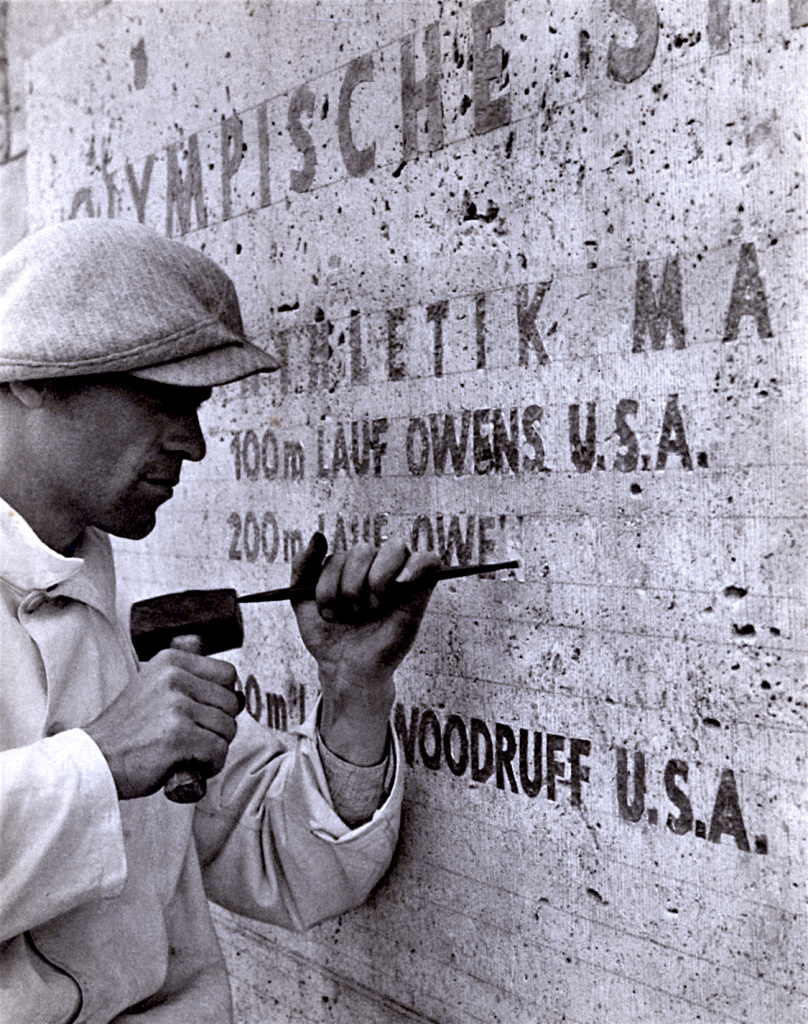

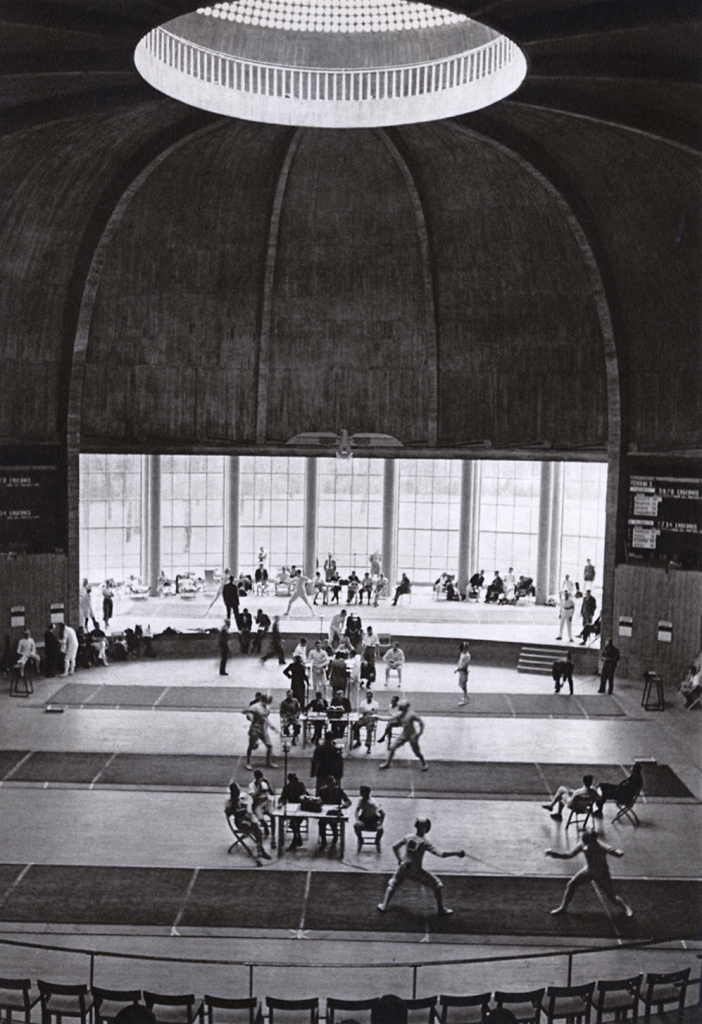

The images produced will be printed in a book, Olimpiadi 1936, published in Italy by Bompiani: a text by Bruno Roghi; notes in three episodes by the same Wolff; 111 images; accurate tables with technical data of each photograph published (lens, shutter speed, aperture and lighting conditions) and the ranking of races.

The photographs that follow are taken from that book which marks an important chapter in the literature of the Olympic photography, the first.

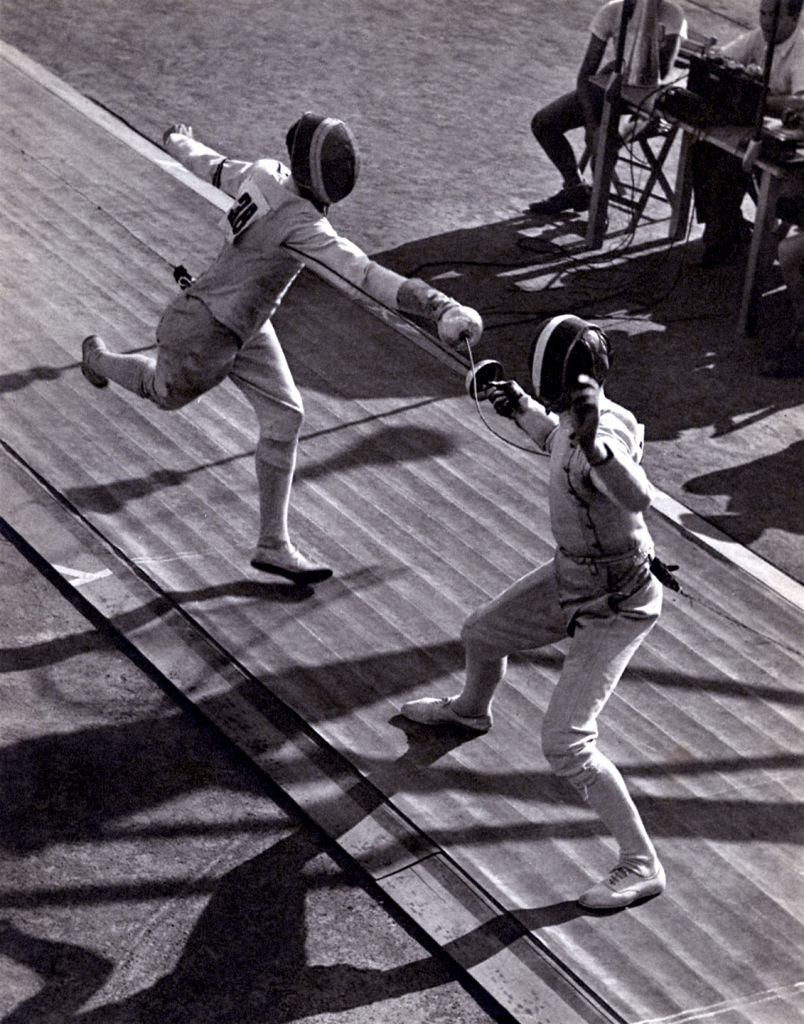

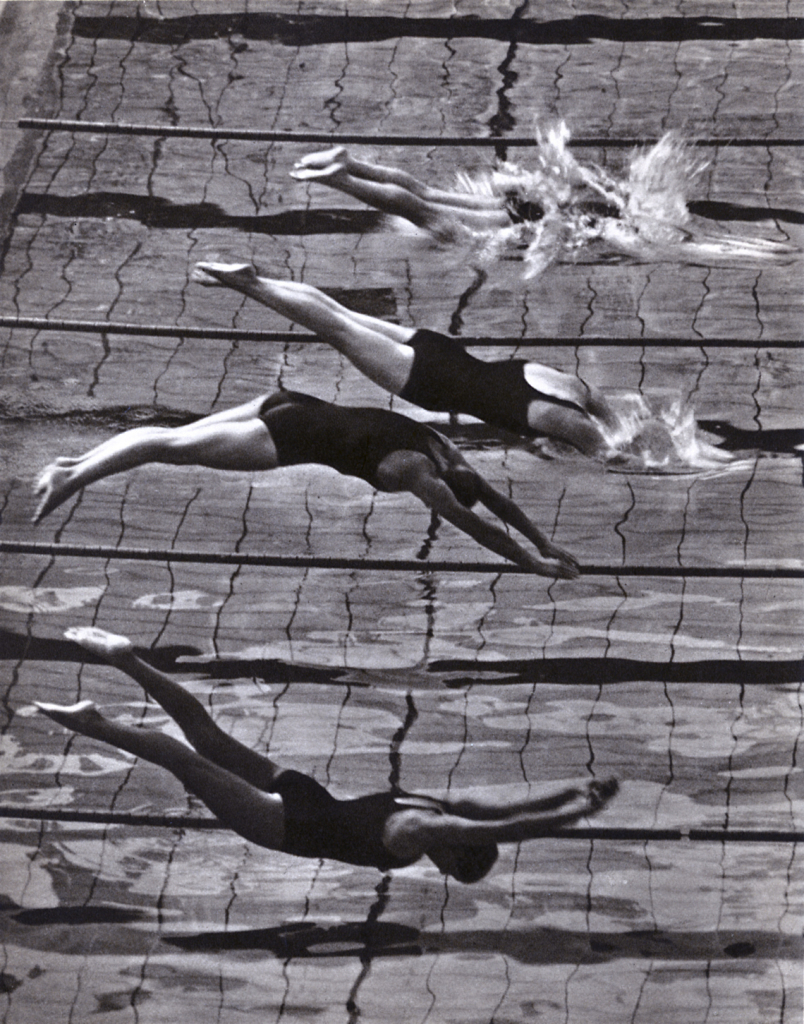

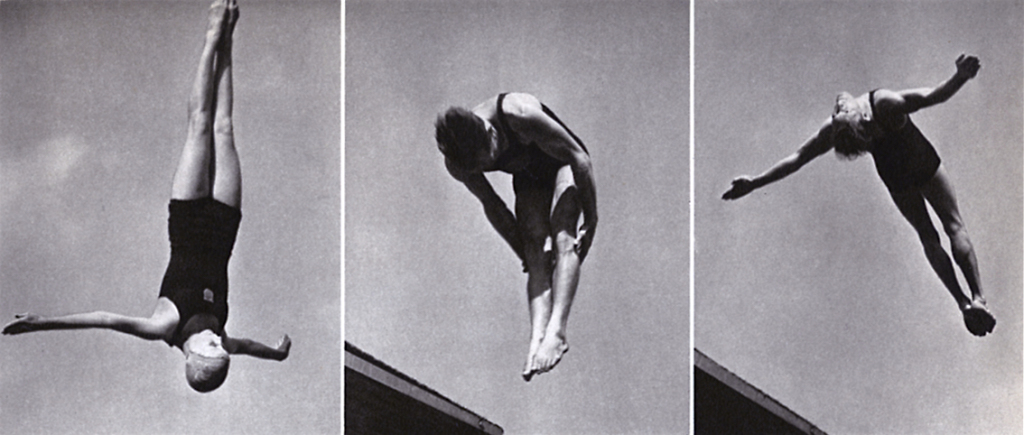

The prose by Roghi, the most famous sports journalist of his era, and director of La Gazzetta dello Sport, is peppered with the rhetoric of those years. The Italians arrived at the Games with a fresh Empire (Addis Ababa fell on 5th May) and in the unofficial nations rankings they finished in third place behind Germany and the United States. They won in football, fencing and Ondina (Raimonda) Valla from L’Aquila, the flying mummy, fastest in the obstacle race.

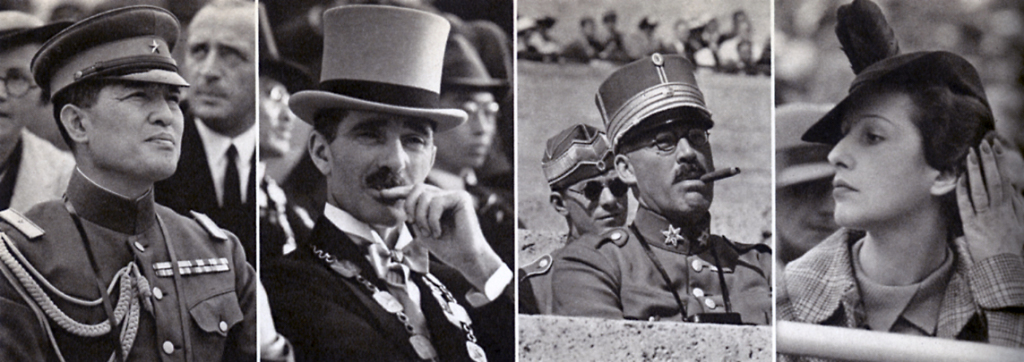

“And if we came to Berlin it was also, and above all, to prove to the people of every race that the most vile enemy, the Sanctions, were far from breaking our bones, we had faced, unmasked, beaten in the Stadium of Honour, for Italy’s glory.” writes Roghi. But, as he knows the job, he also adds the game numbers: 53 countries, 20 sports, 5 thousand athletes, 131 hectares of sports facilities.

The words of Roghi are followed by those of Wolff and here comes the fun part. He complains of the bureaucracy in the accreditation for photographers (red bracelet and white bracelet for the different sectors with the impossibility to exchange them); intransigence of the people responsible at the gates; the grievances of the spectators who sat behind him each time, in order to take a picture, he stands up; and, above all, the inadequacy of the lenses, even the most sophisticated available at that time, for events of this kind. His most powerful telephoto lens, the Telyt/Leitz 20 cm. (today we would say 200mm.) mounted on one of the three Leicas around his neck, the evidence shows, is not responding to the needs of sports photography in stadiums of that size. And for good measure, as always topical photographers remark, there are also problems with the light that is (almost) never the right one.

However, with astonishing vividness, Wolff also captivates the strong emotions that an event of this kind provoke in him: “I try to hold my camera eye steady, and I feel my hands tremble.” And the anxiety that pervades it: “I do not have time to change the lens… I let a device slip from one hand and at once grasp another one … I hear the clicking of typewriters, the turning of sheets of paper, soft journalist’s voices working feverishly “. He also wants to be the first to distribute the material shot: “With one bound I rush to the gate, I throw myself into the first car, take a seat beside the driver, show him my press card, I tell him he has to drive as fast as possible to take me to my lab installed in Friederichstrasse. Colleagues are waiting for me, they snatch the films from me; two hours later someone rushes, with the photographs, to Tempelhof airport, another to a night train, and a third to the editors of the Berlin newspapers … “.

These stories are almost touching in digital photography era, the one of super telephoto lenses, of transmission “at the speed of thought” of any image on any connected computer … in the universe!

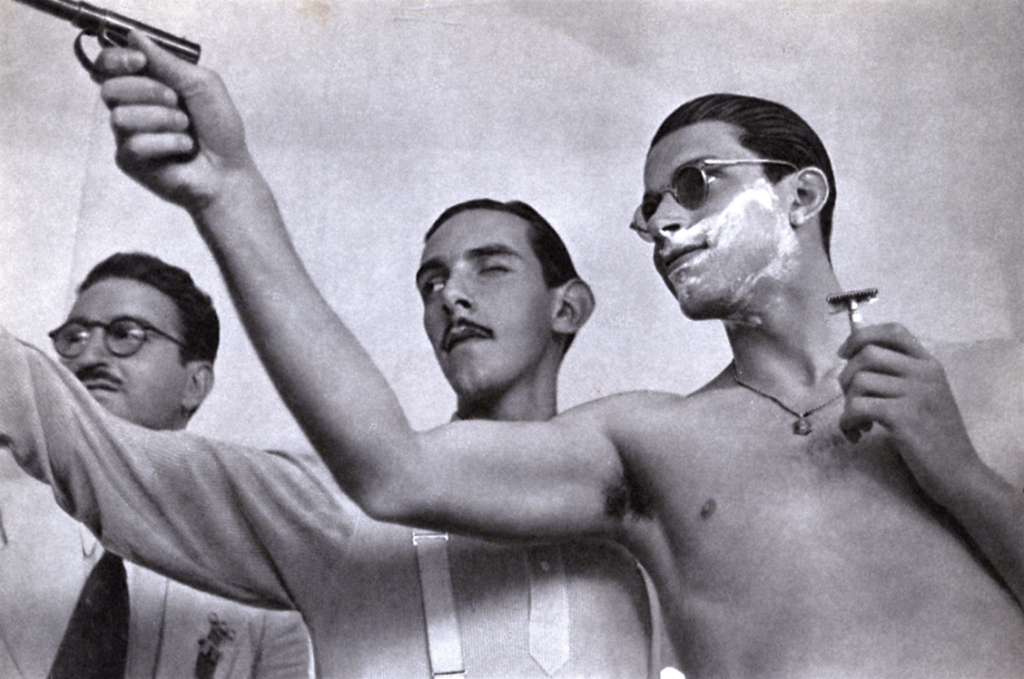

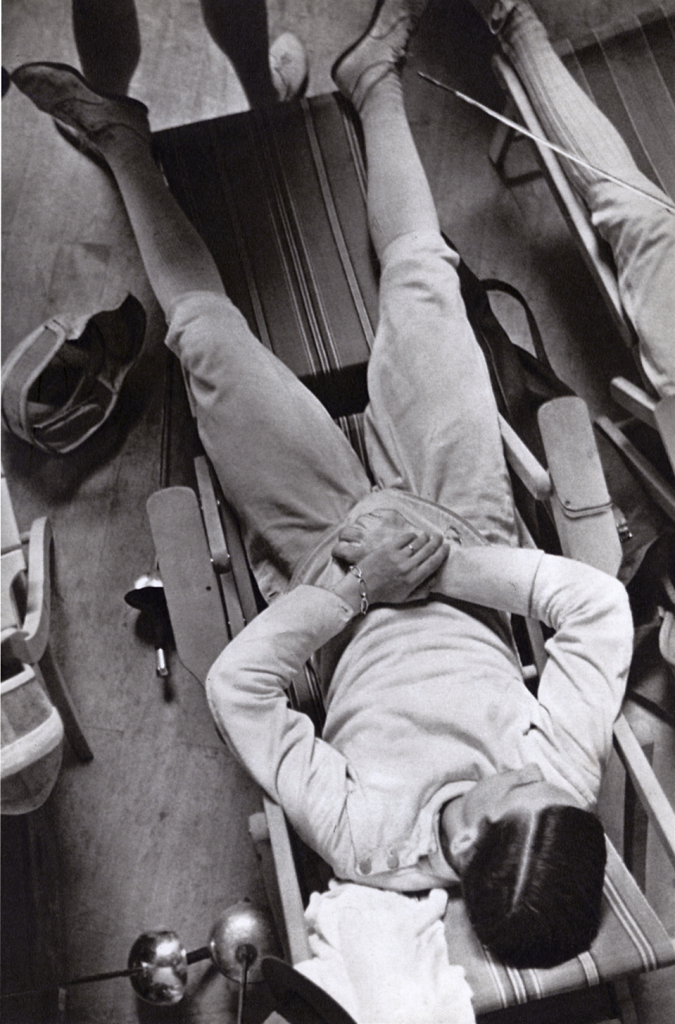

And, just to mention a photo, look at the group portrait that Wolff takes of his colleagues. Some have still in hand, or around the neck, plate cameras with bulky lenses and primitive viewfinders that allow slight approximation of the shots. And the “modern” small Leicas resting on the fronts are equipped with strange “sports” viewfinders that look like self-built. Everyone is waiting for that decisive moment which they will have to grasp, when they have just one shot: nothing like the automatic sequences of dozens of shots per second of the reflex of today!

The photographs of Wolff’s staff, which are not assigned individually to different authors but show a recognizable style (of an artisan workshop, as one would have said in the Renaissance) move us in turn. There is always humanity in the shots, and a bit ‘of “the trade”.

In the book (and in this service) one must not miss a portrait of the most remembered visual interpreter of that edition of the games: Leni Riefenstahl, (not mentioned in the captions), the multi award-winning author of the first documentary shot in an edition of the Games, Olympia (1938). As we see the young woman, who joins one of her cameramen on a comfortable scaffolding built just for her, has her watchful eye on the competition, and holds, in her right hand, something that has the air of being a distance command! In short, the operator points and focuses, but she is there to kick off the filming!