Paul Wolff is an author too often ignored by many “History of Photography of the 1900s”. In effect Paul Heinrich August Wolff, born in Mülhausen, today Mulhouse, in Alsace, on February 19th 1887, and died in Frankfurt on 10th April 1951. I would love to believe in reincarnation and associate that date with the one I was born on, two days later…

Paul Wolff graduated in medicine in Strasbourg in 1914, before being hit by the virus of photography, that forced him to swap his stethoscope with a Leica… A biographer less “involved” than the one writing, perhaps, would address the problem that arose after the First World War, when a German graduated in a university that then became became French was not granted permission to practice in Germany; but let’s be satisfied with the first version, which is much more romantic.

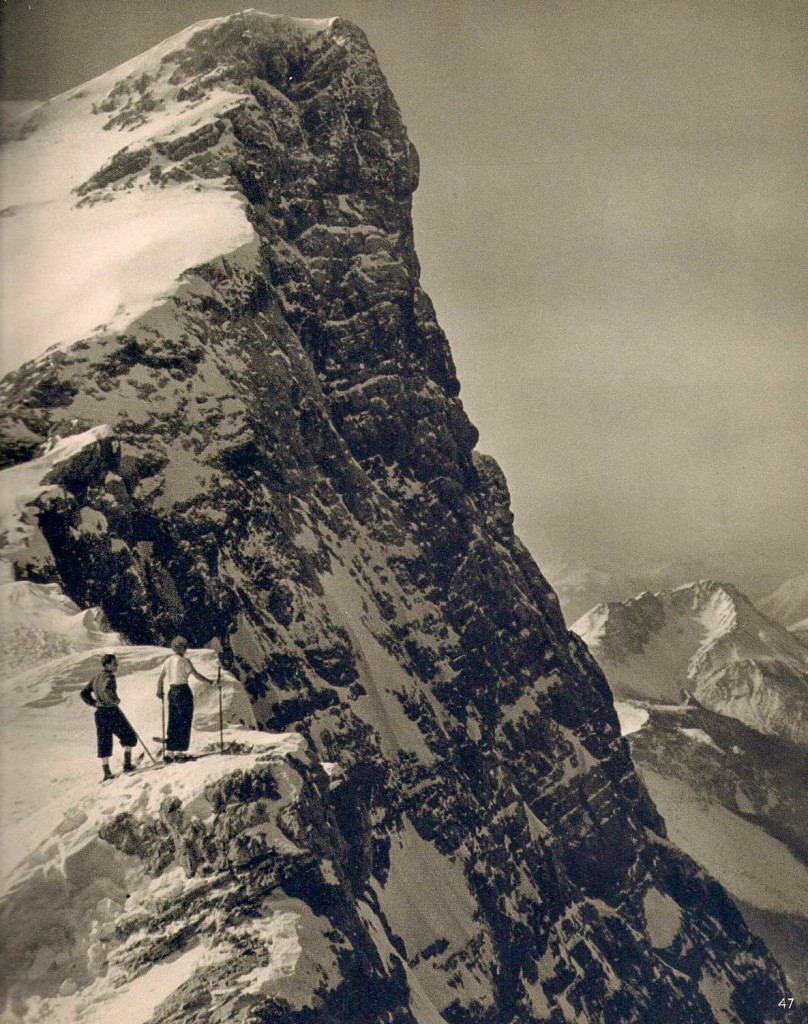

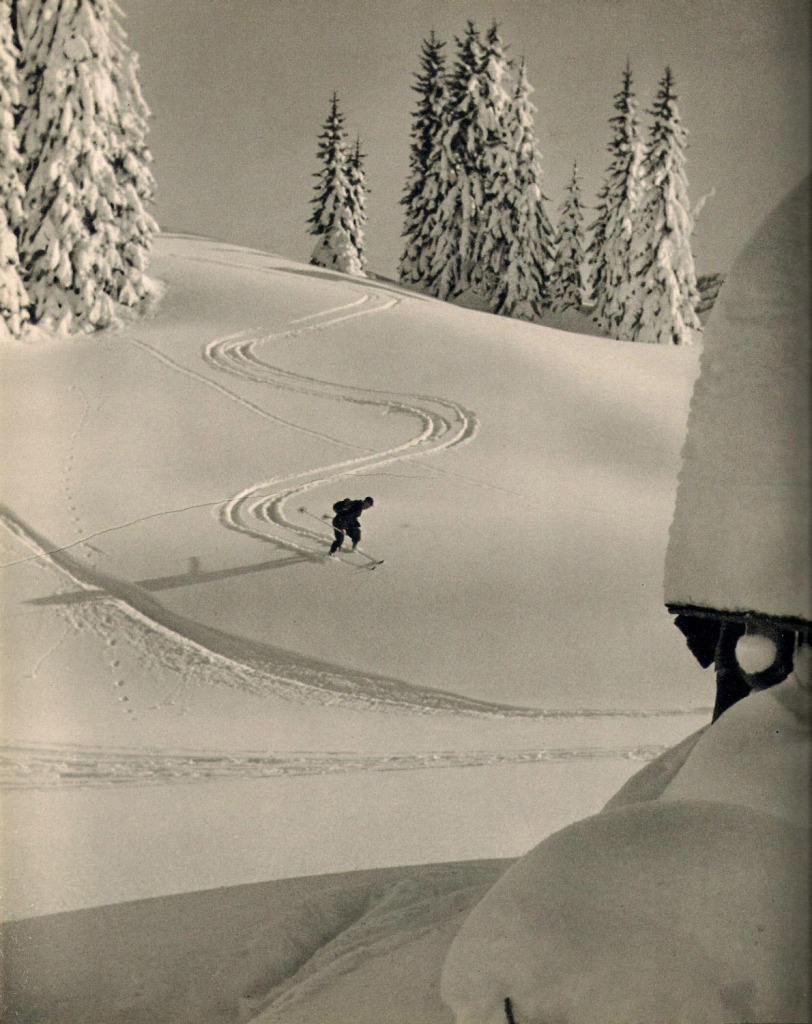

So Paul, who was a 100% doctor, and that always signed his pictures putting Dr. in front of his name, decided after the war to become a professional photographer and to produce documentary films (he had the eye and the technique: he had taken his first photographs at 12 years old!). He works with a 18x24cm. plate camera and produces images of such a level that when Ernst Leitz and Oskar Barnack, respectively manufacturer and inventor of the Leica, in 1924, decided to entrust to a selected number of photographers and technicians, to be exact to 31, prototypes of their “mini camera”, Paul is one of the elected. Along with a Frenchman… a certain Henri Cartier Bresson. Tests encourage assumptions of the designers and the Leitz introduces the Model A during the trade fair in Leipzig, in the spring of 1925. That same year, it sold 1,000. Paul understands immediately what the Leica is capable of, and produces innovative images. They are spontaneous and with unusual camera’s view angles. The small, easy to handle, Leica allows the practice of a “modern” language unhampered with the encumbrance problems of competitors. At the exhibition Die Kamera (The Camera), promoted by Leitz in 1935 at the Rockefeller Center in New York to demonstrate the quality of the images produced with the jewel manufactured in Wetzlar (the prints on the walls are enlargements of 40×60 cm.), Paul is the protagonist. Is the problem of the Leica format the grain highlighted on the prints from enlarging negatives that are so small? He experimented with new formulas of development, by increasing the dilution of the chemical products and lengthening the time of “immersion” in the first bath, and uses only very low sensitivity (10 ISO) films. His black and white shots have a very wide range, and even when he starts with colour, with Agfacolor, he gets amazing results.

Leitz has chosen well. Wolff becomes the functional testimonial of the new format. The accuracy of the shots and versatility can be compared, in documentary photography, publishing and advertising, to the genius, perhaps unequaled, of the American Margarethe Bourke White (1904-1971) who will sign the first cover of Life on November 23rd, 1936. For other coincidences see under! The Wetzlar’s company supports and pampers Wolff relentlessly. They entrust him with the new lenses as soon as they are produced and have not yet been distributed so that he achieves the images for advertising these; more, organize international tours for the screening of his especially made slides. So they use the Alsatian photographer’s ability with targeted operations of what today is called marketing and he reciprocates the generosity of the firm producing photographs that few others would be able to shoot.

In 1934, Paul’s book Meine Erfharungen mit der Leica (My experiences with Leica) is a great success, thanks also to the 50 thousand copies printed (another one, similar, with only colour photographs will follow in 1940). Two years later Paul photographed the Berlin Olympics. This will bring to the book “Was ich bei den Spielen Olympischen 1936 sah (What I saw at the 1936 Olympic Games). In a photograph of the volume another great reporter of that edition of the games appears, Leni Riefenstahl, during the shooting of the film which will become “Olympia“. Do the two know each other? If I had known of Wolff in 1990, when I interviewed Leni, I would have asked her!

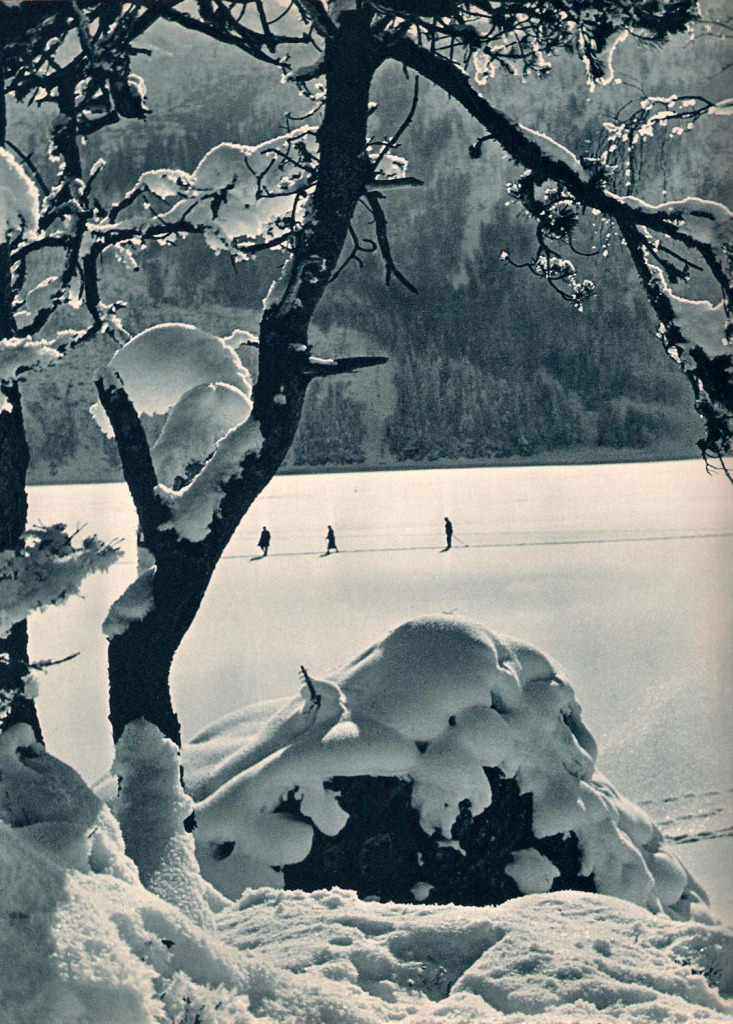

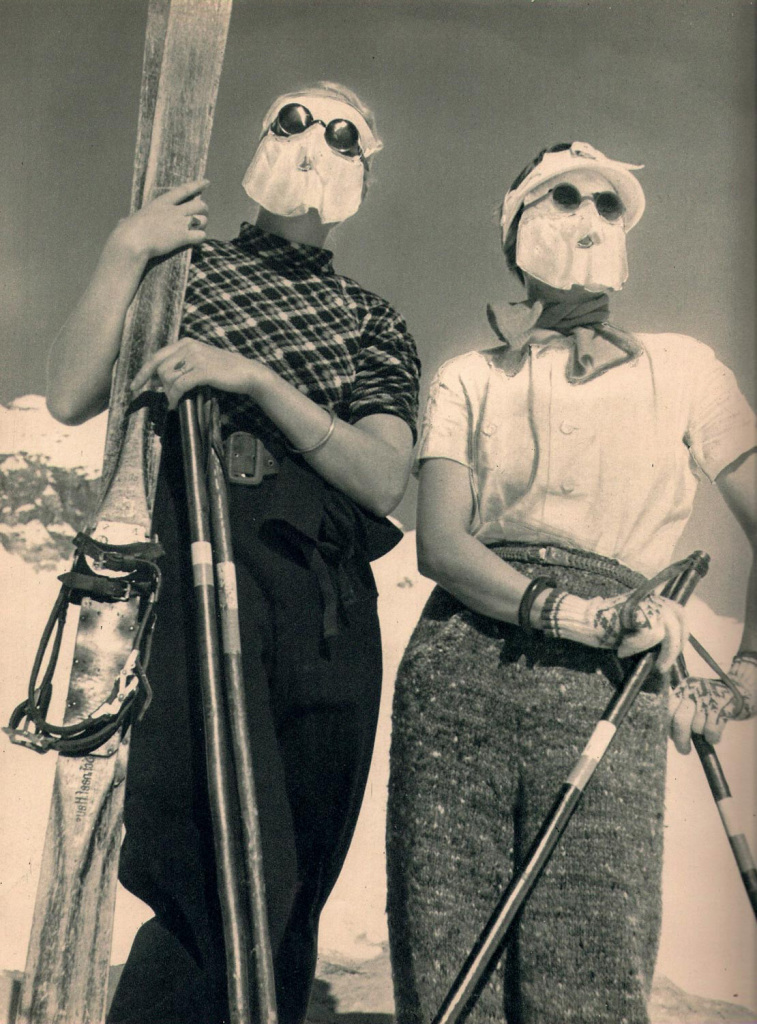

In 1936, however, the agency / laboratory, Dr. Paul Wolff & Tritschler, founded in 1927, with Alfred Tritschler precisely, has 20 employees: an index of the success of the doctor who had, in a Europe dedicated to the wars, to strip off his white coat to dedicate himself to light and shadow. In the same year Time publishes his cover picture of a Hitler that flaunts the palm of his right hand. Moreover, the photographer did not like the character. Instead cars were to become a passion: he photographs them always with great attention. He signs very innovative campaigns for Audi and baptizes the first book in colour created for the German firm Opel for which he had already produced a book in black and white and in a limited edition Opel I’m Sport 1934 (Opel in sport in 1934). Even glamor photography finds an excellent interpreter in him that does not seem to be lacking in irony. He masters not only reading light, and the choice of optics, but is very good with the technique of selective focusing, which seems rather complicated with a rangefinder camera. His direction in the development of the scene to photograph is masterful. The backlight does not intimidate him at all!

World War II spares him, but much of his archive goes up in smoke as a result of the bombs dropped on Frankfurt in 1944. There are very few original prints that are saved. Those preserved in the archives of the magazines that had been sent for publication are delivered to the future. Very few, however. Unfortunately.